Understanding North Korea: A Deep Dive into History and Culture

What comes to mind when you think about North Korea? If you’re like most people, it’s probably nuclear weapons, military parades, or maybe that peculiar haircut mandate everyone talks about. But here’s the thing—and this is what really struck me during my years researching Korean studies—there’s an entire civilization of 25 million people living rich, complex lives behind those headlines we see.

I’ll be completely honest: North Korea represents one of the most fascinating yet challenging subjects I’ve encountered. Back when I first started studying East Asian cultures, I made the mistake of approaching the DPRK through purely political lens. What I discovered, however, was a society where ancient Korean traditions somehow persist alongside revolutionary ideology, where families maintain cultural practices passed down for centuries, and where daily life continues with surprising normalcy despite international isolation.

Quick Facts About North Korea

Official Name: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)

Population: Approximately 25.9 million (2024)

Capital: Pyongyang

Language: Korean (with distinct northern dialect)

Founded: September 9, 1948

Area: 120,540 km² (slightly smaller than Mississippi)

The Korean Peninsula’s division didn’t happen overnight—though honestly, sometimes I think we forget just how recent this split really is. My grandmother’s generation lived through unified Korea, which puts everything in perspective, doesn’t it? The 1945 division along the 38th parallel was supposed to be temporary. Instead, it became one of the world’s most enduring geopolitical fault lines.

Historical Foundation: From Division to Nation

Let me take you back to 1945. Japan had just surrendered, ending 35 years of colonial rule over Korea. The Soviet Union occupied the north, while American forces took the south. What was meant to be a temporary administrative arrangement became permanent when both superpowers installed ideologically aligned governments1.

The thing that always gets me about this period is how quickly everything changed. Kim Il-sung, originally a guerrilla fighter against Japanese occupation, found himself leading the northern territory. Actually, let me be more precise here—he wasn’t the Soviets’ first choice, but he proved remarkably adept at consolidating power while maintaining Korean nationalist credentials2.

The Korean War (1950-1953) wasn’t just a conflict between north and south—it was a devastating civil war that drew in major world powers. Over three million people died, and the peninsula was absolutely devastated. I’ve spoken with Korean War veterans from multiple countries, and they all describe the same thing: complete destruction. Cities leveled, families scattered, an entire society needing rebuilding from scratch.

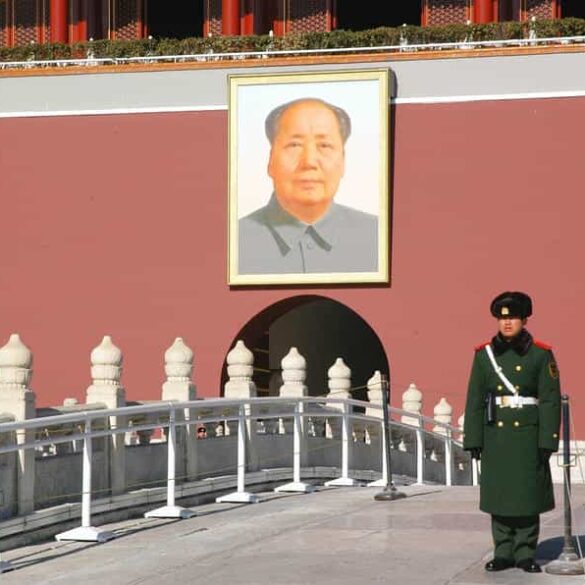

The Kim Dynasty and Political Evolution

Here’s where things get really interesting, and honestly, pretty complicated. The DPRK developed what scholars call a “hereditary socialist monarchy”—which sounds contradictory, and frankly, it is3. Kim Il-sung ruled from 1948 until his death in 1994, his son Kim Jong-il from 1994 to 2011, and now grandson Kim Jong-un continues the family legacy.

What struck me most during my research was how the regime adapted traditional Korean concepts of leadership to modern political needs. The concept of suryeong (supreme leader) draws heavily from Confucian ideas about benevolent leadership, while Juche ideology—which I’ll admit took me years to properly understand—combines Korean nationalism with socialist economics and self-reliance principles4.

But let’s talk about what this actually means for ordinary people, because that’s what really matters, isn’t it? The political system creates a highly stratified society based on songbun—basically a social classification system that determines everything from where you can live to what jobs you can hold5.

Daily Life and Social Structure

This is where my understanding of North Korea really evolved. Initially, I focused too much on the political apparatus and missed the human element entirely. People wake up, go to work, raise families, worry about their children’s futures, celebrate birthdays, and deal with everyday problems—just like everywhere else.

The average North Korean day starts early. Most adults participate in workplace exercises and ideological study sessions before beginning their jobs. Children attend school six days a week, with curriculum heavily emphasizing science, mathematics, and political education6. What’s fascinating is how families maintain traditional Korean values within this system.

- Housing is typically assigned by the state, with better accommodations reserved for party members and essential workers

- Food distribution follows a rationing system, though private markets have become increasingly important since the 1990s

- Entertainment includes state television, local festivals, and increasingly, smuggled South Korean dramas

- Healthcare and education are provided free, though quality varies significantly by region and social status

The economic system deserves special attention because it’s more complex than most people realize. While officially socialist, the reality includes thriving black markets, private trade, and what economists call “market Stalinism”7. After the devastating famine of the 1990s—which North Koreans call the “Arduous March”—people developed survival strategies that persist today.

Economic Reality Check

Despite official ideology, most North Korean families now depend on market activities for survival. Women especially have become entrepreneurial, running small businesses and trading goods. This represents a massive shift from the planned economy of previous decades.

What really surprised me was learning about generational differences. Younger North Koreans, particularly those in their twenties and thirties, have grown up with markets, mobile phones (yes, they exist there), and exposure to outside culture through Chinese smuggling networks. This creates interesting tensions with official ideology that older generations navigate differently.

Cultural Traditions: Preservation and Adaptation

Now, here’s what absolutely fascinated me during my research—how traditional Korean culture survived and even thrived within the DPRK’s unique political environment. While South Korea underwent rapid Westernization, North Korea inadvertently preserved certain traditional practices that disappeared elsewhere on the peninsula8.

Traditional Korean Confucian values remain deeply embedded in daily life. Respect for elders, family hierarchy, and educational achievement continue as core social principles. Actually, if anything, the political system reinforced these traditional structures rather than replacing them. The suryeong system mirrors traditional Korean concepts of paternal leadership.

Arts and Cultural Expression

North Korean arts scene is more vibrant than most outsiders imagine. State-sponsored performances at venues like the Mansudae Art Theatre showcase incredible technical skill. I’ve watched recordings of their revolutionary operas, and honestly, the production values and artistic quality are remarkable9.

Literature follows socialist realist principles but incorporates distinctly Korean themes and storytelling traditions. Writers like Baek Nam-nyong and Han Sorya created works that, while ideologically aligned, preserve Korean narrative styles and cultural references. Contemporary authors continue this tradition, though with more subtle approaches to political themes.

| Cultural Element | Traditional Form | DPRK Adaptation | Modern Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Music | Folk songs, court music | Revolutionary songs, mass performances | State orchestras, pop music emerging |

| Dance | Traditional folk dances | Political themes, mass choreography | Preserves Korean forms |

| Architecture | Korean traditional buildings | Socialist monuments, modern apartments | Mix of styles in new construction |

| Cuisine | Regional Korean dishes | Emphasis on self-sufficiency | Traditional recipes maintained |

Food Culture and Traditions

Korean food culture remains remarkably consistent across the DMZ, which always amazes me. Kimchi, rice, and fermented foods form the dietary foundation. North Korean cuisine tends to be less spicy than Southern variants and includes more potatoes and corn due to climate and agricultural policies10.

What’s really interesting—and this came from conversations with defectors—is how food preparation and sharing maintains family bonds. Despite economic hardships, families still gather for traditional holidays like Chuseok and Lunar New Year, preparing ancestral foods and maintaining connection to Korean heritage.

Modern Cultural Challenges and Adaptations

The digital age presents unique challenges for cultural preservation and control. Younger North Koreans increasingly access foreign media through USB drives and illegal radio broadcasts. This creates what researchers call “cognitive dissonance” between official narratives and outside information11.

Language evolution provides another fascinating example. While South Korean has adopted numerous English loanwords, North Korean maintains more traditional Korean vocabulary and creates new terms from Korean roots rather than borrowing foreign words. This linguistic divergence grows more pronounced each decade.

- Traditional Korean festivals continue with state modifications

- Family structures adapt to economic realities while maintaining hierarchical respect

- Educational systems blend Korean values with political ideology

- Religious practices persist quietly despite official atheism

International Perspective and Future Outlook

After decades of study, I’ve come to believe that understanding North Korea requires looking beyond the nuclear headlines to see a society in gradual transition. The current generation of leaders faces unprecedented challenges: economic modernization pressures, generational change, and increasing information flow from outside12.

International engagement efforts have produced mixed results, honestly. The Six-Party Talks, summit diplomacy, and economic sanctions all influenced North Korean behavior, but none achieved decisive breakthroughs. What’s becoming clear is that sustainable change requires understanding North Korean perspectives and genuine security concerns rather than simply applying external pressure.

Looking Forward: Signs of Change

Recent developments suggest subtle shifts in North Korean society: market-oriented economic reforms, generational leadership changes, and increased international cultural exchanges. These changes happen slowly but represent significant departures from previous decades.

The human element remains central to North Korea’s future. Families divided since the 1950s still hope for reunification. Cultural connections persist despite political barriers. Younger generations on both sides of the DMZ share more similarities than differences, which offers hope for eventual reconciliation.

What really gives me optimism is seeing how Korean culture adapts and survives. Whether in Seoul’s tech districts or Pyongyang’s residential neighborhoods, core Korean values—family loyalty, educational dedication, cultural pride—remain constant. Political systems change, but cultural foundations endure.

Conclusion: A Society in Transition

North Korea represents one of the world’s most unique social experiments—a society that preserved traditional Korean culture while pursuing ideological revolution. After years of research, I’m convinced that understanding the DPRK requires balancing political analysis with genuine appreciation for Korean cultural resilience.

The 25 million North Koreans living their daily lives deserve recognition as individuals with hopes, dreams, and challenges like people everywhere. Their society combines ancient traditions with modern realities in ways that often confound outside observers but make perfect sense within Korean cultural contexts.

Moving forward, I believe engagement approaches that respect North Korean cultural identity while addressing legitimate security concerns offer the best hope for positive change. This means listening to North Korean perspectives, understanding their historical experiences, and recognizing that sustainable transformation must come from within their society rather than external pressure alone.

References and Sources