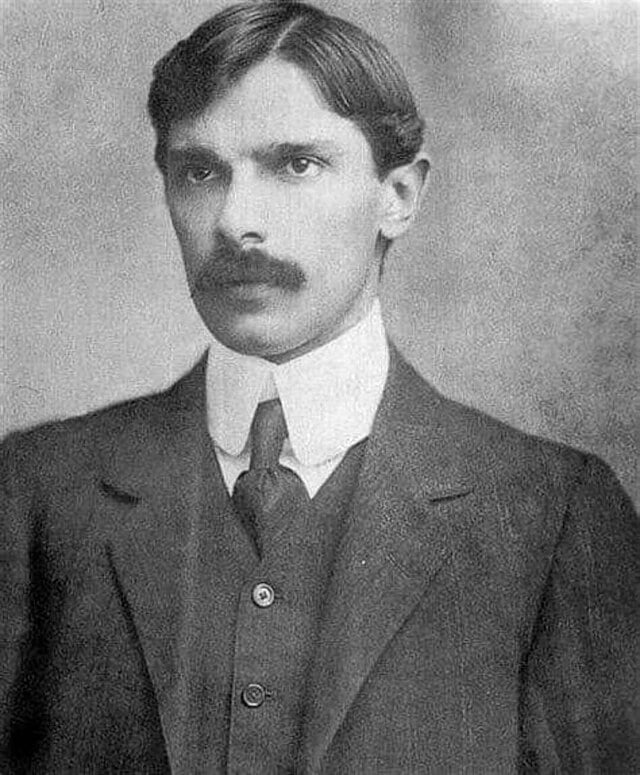

Muhammad Ali Jinnah: The Fascinating Founder of Pakistan

Here’s something that always fascinates me about history—sometimes the most unlikely people end up changing the world completely. Muhammad Ali Jinnah? Perfect example. This impeccably dressed lawyer who loved Shakespeare and spoke English better than most Brits somehow became the architect of one of the most dramatic political transformations of the 20th century.

I’ll be honest, when I first started researching Jinnah years ago, I expected another typical politician’s story. Boy, was I wrong. This man’s journey from secular lawyer to “Quaid-e-Azam” (Great Leader) is absolutely riveting—full of unexpected twists, brilliant legal maneuvers, and enough political drama to fill a dozen Netflix series.

Why Jinnah Still Matters Today

Understanding Jinnah isn’t just about Pakistani history—it’s about how one person’s vision can literally reshape the world map. His story offers crucial insights into leadership, negotiation, and the complex process of nation-building that remains relevant for modern politics and international relations.

The Unlikely Revolutionary: Early Life and Legal Career

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was born on December 25, 1876, in Karachi—and here’s where things get interesting right from the start. His father, Jinnahbhai Poonja, was a successful merchant who initially wanted his son to follow in the family business. But young Jinnah had other plans, and frankly, his determination at such a young age is pretty impressive.

At just 16 years old—can you imagine?—Jinnah convinced his parents to let him study law in London. This wasn’t just unusual for the time; it was practically unheard of. Most families wouldn’t dream of sending their teenage son halfway across the world, but Jinnah was already showing that persuasive ability that would later reshape South Asia.

What strikes me most about Jinnah’s London years is how thoroughly he embraced Western culture and education. He studied at Lincoln’s Inn, one of the most prestigious legal institutions in the world, and became the youngest Indian to be called to the bar in 18961. But here’s the fascinating part—while he was mastering English law and adopting Western dress and manners, he was also developing a deep appreciation for constitutional principles that would later prove crucial in his political career.

When Jinnah returned to India in 1896, he initially struggled to establish his legal practice. Actually, let me be more precise about this—he really struggled. His first case was a complete disaster, and he was so nervous that he couldn’t even speak properly in court2. It’s hard to imagine the future founder of Pakistan being tongue-tied in a courtroom, but that’s exactly what happened.

However, Jinnah’s persistence paid off spectacularly. By the early 1900s, he had become one of India’s most successful lawyers, earning enormous fees and developing a reputation for meticulous preparation and brilliant cross-examination. Colleagues often mentioned how he could dissect the weakest points in opposing arguments with surgical precision.

| Year | Achievement | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1896 | Called to the Bar | Youngest Indian barrister |

| 1900 | Established practice | Became leading advocate |

| 1905 | Entered politics | Joined Indian National Congress |

The transformation from struggling young lawyer to legal powerhouse is remarkable enough, but what really gets me excited about this period is how Jinnah’s legal training shaped his entire approach to politics. He understood constitutions, precedents, and the importance of precise language in a way that most politicians of his era simply didn’t. This legal foundation would prove absolutely crucial when he later negotiated the creation of Pakistan.

The Political Awakening: From Congress to Independence

Now here’s where Jinnah’s story takes a completely unexpected turn. In 1905, he joined the Indian National Congress as a moderate member—and I mean moderate in the truest sense. This wasn’t the fiery revolutionary we might expect from a future nation-founder. Early Jinnah was actually promoting Hindu-Muslim unity and working within the existing British system for gradual reform.

What’s fascinating is how different Jinnah was from his contemporaries. While other leaders were organizing mass movements and protests, Jinnah believed in constitutional methods and legal processes. Honestly, his approach was so measured and diplomatic that many people initially underestimated his potential impact. Big mistake.

The Lucknow Pact: Jinnah’s Masterpiece

In 1916, Jinnah orchestrated the Lucknow Pact between the Congress and Muslim League—a diplomatic achievement that earned him the title “Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity.” This agreement on separate electorates and Muslim representation showcased his negotiation skills that would later prove crucial in creating Pakistan.

The period from 1910 to 1920 represents what I consider Jinnah’s golden age as a unifying leader. He genuinely believed that Hindus and Muslims could work together in a united India, and his efforts to bridge communal divides were remarkable3. The Lucknow Pact of 1916 stands as perhaps his greatest early achievement—bringing together the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League in a way that seemed impossible.

But then came Gandhi, and everything changed. I’ve always found the Gandhi-Jinnah relationship absolutely fascinating because it represents one of history’s great philosophical clashes. Gandhi’s mass movement approach, with its emphasis on non-cooperation and civil disobedience, was completely at odds with Jinnah’s constitutional methods.

Here’s what really gets me about this period—Jinnah initially tried to work with Gandhi. He attended Congress meetings, participated in discussions, and genuinely attempted to find common ground. But Gandhi’s approach, which Jinnah saw as mob rule and religious revivalism, went against everything he believed about proper political conduct.

The breaking point came in 1920 when Gandhi launched his Non-Cooperation Movement. Jinnah stood up in Congress and delivered what many consider one of his most important speeches, arguing that mass movements would lead to chaos and violence4. When the Congress rejected his constitutional approach, Jinnah made a decision that would change the course of history—he resigned from the Congress.

What followed was what historians call Jinnah’s “wilderness years”—roughly 1920 to 1935. During this period, he largely withdrew from active politics, focusing on his legal practice and spending considerable time in London. Many people thought his political career was over. Actually, some of his biographers suggest he was genuinely disillusioned with Indian politics altogether.

- Withdrew from active Congress participation after 1920

- Spent extended periods in London developing international legal practice

- Maintained minimal involvement with Muslim League during this period

- Observed rising Hindu-Muslim tensions with growing concern

But here’s the thing about Jinnah—he was always watching, always analyzing. During his time in London, he kept close tabs on developments in India, and what he saw increasingly convinced him that his original vision of Hindu-Muslim unity was becoming impossible. The rise of Hindu nationalism, communal riots, and what he perceived as Congress’s Hindu-centric policies were reshaping his entire worldview.

The 1930s marked Jinnah’s gradual return to active politics, but this time with a completely different agenda. The All-India Muslim League, which had been largely dormant, suddenly found itself with a dynamic leader who brought both legal expertise and political acumen. By 1934, Jinnah was elected as the League’s permanent president, and the transformation from advocate of unity to champion of Muslim separatism was complete.

What strikes me most about this evolution is how methodical it was. Jinnah didn’t suddenly wake up one day and decide to create Pakistan. Instead, his changing views reflected a careful analysis of political realities, demographic trends, and what he saw as the inevitable outcome of majoritarian democracy in a religiously diverse society5.

Creating Pakistan: The Impossible Dream Made Reality

Alright, here’s where Jinnah’s story becomes absolutely incredible. In 1940, at the Muslim League’s Lahore session, he endorsed what became known as the Pakistan Resolution—demanding separate nation-states for Muslims in South Asia. The audacity of this proposal still takes my breath away. We’re talking about partitioning the British Empire’s crown jewel, displacing millions of people, and creating entirely new nations. Most people thought it was impossible.

But Jinnah had done his homework. He understood that the British were war-weary and economically exhausted, that Indian independence was inevitable, and that Muslim political representation would be permanently marginalized in a Hindu-majority democracy. His legal training showed here—he was building a case, methodically assembling evidence and arguments.

Pakistan Today: Jinnah’s Vision Realized

Modern Pakistan, with a population of over 220 million people, stands as the world’s second-largest Muslim nation and fifth-most populous country. From its capital Islamabad to the bustling port city of Karachi where Jinnah was born, the country continues to embody his vision of a separate homeland for South Asian Muslims.

The 1940s represent Jinnah at his absolute political peak. What amazes me is how he managed to transform the Muslim League from a elite debating society into a mass political movement. The 1946 provincial elections were a masterclass in political organization—the League won 425 out of 476 Muslim seats, giving Jinnah an unassailable mandate6.

But here’s what most people don’t realize about the Pakistan creation process—it wasn’t just about religious differences. Jinnah articulated a sophisticated political theory about minority rights, federal structures, and the dangers of majoritarian democracy. His famous “Two-Nation Theory” was as much about political science as it was about religious identity.

The negotiations with the British and Congress leaders during 1946-47 showcase Jinnah’s remarkable diplomatic skills. Lord Mountbatten, the last British Viceroy, initially tried to charm Jinnah into accepting a united India. What he discovered was that Jinnah was absolutely unmovable when he believed he was right. Mountbatten later described him as one of the most formidable negotiators he had ever encountered7.

The final months before partition were incredibly dramatic. Jinnah was simultaneously negotiating with multiple parties—British officials, Congress leaders, provincial governments, and his own Muslim League colleagues. The complexity of these discussions, involving everything from military assets to railway lines, required exactly the kind of detailed legal mind that Jinnah possessed.

- Secured separate nation status through sustained political pressure

- Negotiated territorial boundaries despite limited bargaining power

- Established governmental structures in record time

- Managed massive refugee crisis during partition

When Pakistan finally came into existence on August 14, 1947, Jinnah became its first Governor-General. But here’s where the story takes a poignant turn—he was already seriously ill with tuberculosis and lung cancer. The man who had spent decades fighting for Pakistan’s creation had less than a year to shape its early development.

What he accomplished in those final months is remarkable. Jinnah established the basic governmental framework, delivered his famous speech about religious freedom and equal citizenship, and tried to set Pakistan on a path toward becoming a modern, democratic state. His vision wasn’t a theocracy—it was a constitutional democracy where religious minorities would have full rights.

The Partition Challenge

Creating Pakistan required dividing British India’s assets, including 175,000 miles of railway track, 4,000 government offices, and military equipment worth millions of pounds. Jinnah’s team had to build a nation from scratch while managing the largest migration in human history—over 10 million people crossing new borders.

The human cost of partition was devastating—hundreds of thousands died in communal violence, and millions became refugees overnight. This tragedy often overshadows Jinnah’s achievement, but it’s important to understand that he consistently advocated for peaceful population transfer and protection of minorities. The violence that erupted was largely beyond his control, though it deeply affected him personally.

Looking back at this period, I’m struck by how Jinnah managed to maintain his vision despite enormous pressures. He could have easily given in to extremist demands or abandoned his secular constitutional approach. Instead, he stuck to his principles even when it made him unpopular with some of his own supporters8.

The Enduring Legacy: Jinnah’s Impact on Modern South Asia

Muhammad Ali Jinnah died on September 11, 1948, just 13 months after Pakistan’s creation. But here’s what absolutely fascinates me about his legacy—in just over a year as Governor-General, he established principles and precedents that continue to influence Pakistani politics today. His final speech to the Constituent Assembly remains one of the most quoted documents in Pakistani constitutional history.

What really gets me thinking about Jinnah’s long-term impact is how his vision of Pakistan differed from what actually developed. He envisioned a secular state with religious freedom, strong institutions, and constitutional governance. Reality proved more complicated, but his original principles continue to inspire Pakistani democrats and reformers9.

Honestly, when I consider Jinnah’s place in world history, I think he deserves recognition alongside other great nation-builders like George Washington or Nelson Mandela. Creating a nation from scratch, especially under such challenging circumstances, requires extraordinary political skills and unwavering determination. The fact that Pakistan survived its tumultuous early years and developed into a nuclear power speaks to the solid foundations Jinnah established.

Modern scholarship on Jinnah has become increasingly nuanced, moving beyond simple hero-worship or demonization. Recent biographers like Stanley Wolpert and Akbar Ahmed have highlighted his complexity—a man who was simultaneously a secular constitutionalist and a champion of religious identity, a Westernized lawyer who became an Asian nationalist leader10.

The lessons from Jinnah’s career extend far beyond Pakistani history. His emphasis on constitutional methods, minority rights, and institutional building offers valuable insights for anyone interested in political development and nation-building. His transformation from a unity advocate to a separatist leader also provides a fascinating case study in how political circumstances can reshape even the most principled positions.

What strikes me most about Jinnah’s legacy is how his personal characteristics—meticulous preparation, unwavering principles, and exceptional negotiating skills—enabled him to achieve what seemed impossible. In an era of mass politics and populist appeals, his constitutional approach proved remarkably effective.

| Aspect | Jinnah’s Approach | Modern Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional Methods | Legal framework over mass movements | Institutional democracy |

| Minority Rights | Protection through separate representation | Pluralistic societies |

| Negotiation Skills | Principled but flexible diplomacy | International relations |

The continuing relevance of Jinnah’s ideas is evident in contemporary debates about minority rights, federalism, and constitutional governance. His warnings about majoritarian democracy resonate in many modern contexts, while his emphasis on legal and institutional solutions remains highly relevant for political development worldwide.

As someone who’s spent years studying South Asian history, I find Jinnah’s story both inspiring and sobering. Inspiring because it demonstrates how individual vision and determination can reshape entire regions. Sobering because it also shows how even the most well-intentioned political changes can have unintended consequences.

What I hope readers take away from Jinnah’s story is an appreciation for the complexity of political leadership and the importance of principled positions in public life. Whether you agree with his ultimate vision or not, his commitment to constitutional methods and minority rights offers valuable lessons for anyone interested in democratic governance and political development11.

References